IN HIS book, “A random walk down Wall Street,” Burton G. Malkiel tells of a botany professor from Vienna who brought to Leyden (a city and municipality in the province of South Holland) a collection of unusual plants that had originated from Turkey.

One night, a thief broke into his house and stole the tulip bulbs which were subsequently sold for a handsome profit. Over the next decade or so, the tulip became a popular but expensive item in Dutch gardens.

Many of these flowers succumbed to a non-fatal virus known as mosaic which caused the petals to develop contrasting colored stripes.

The Dutch valued highly these infected bulbs, called bizarres, and in a short time popular taste dictated that the more bizarre a bulb, the greater its value.

Slowly, “tulip mania” set in. At first, bulb merchants simply tried to predict the most popular variegated style for the coming year.

Then they would buy an extra-large stockpile in anticipation of a rise in price. Tulip-bulb prices began to rise wildly. The more expensive the bulbs became, the more people viewed them as smart investments.

Everyone imagined that the passion for tulips would last forever and buyers from all over the world would come to Holland and pay whatever prices were asked for them.

In the last years of the tulip spree, which lasted approximately from 1634 to 1637, people started to barter their personal belongings such as land, jewellery and furniture, for the bulbs.

Apparently, as happened in all speculative crazes, prices eventually got so high that some people decided they would be prudent and sell their bulbs. Soon, others followed suit and bulb deflation grew at an increasingly rapid pace.

Government ministers stated officially that there was no reason for tulip bulbs to fall in price - but no one listened. Dealers went bankrupt and refused to honour their commitment to buy tulip bulbs.

A government plan to settle all contracts at 10 percent of their face value was frustrated when bulbs fell even below this mark.

You may be amazed and think that this sort of thing will never happen in our time. Well, unfortunately, you will be disappointed.

The crash of 1929

From early March 1928 through early September 1929, the stock market percentage increase in the US equaled that of the entire period from 1923 through early 1928.

Stock market speculation was a national past time. People were borrowing money to buy stock that was way overpriced. On 3rd of September, 1929, the market reached a peak that was not surpassed for a quarter of a century, even though business activities and sentiment have fallen months before.

On 5th September, the market suffered a sharp decline. Even en though bankers and government officials assured the country that there was no cause for concern, the market ignored them. When customers began selling their holdings due to their inability to meet margin calls, the market fell further. Panic reached its peak on 29th October 1929.

Prices fell off the cliff and by the time the lows were reached in 1932, most blue chip stocks had fallen 95 percent.

Similar bouts of market madness occurred from the 60s onwards. In the 60s and 70s, it was about growth stocks such as IBM and Texas Instruments that were sold at ridiculous prices but buyers bought because they firmly believed that many would pay a much higher price. In the 80s, it was about initial public offerings.

This was especially so for biotechnology companies which did not have earnings to show but simply a pipeline of potential products. More recently was probably the biggest bubble of all time - the Internet.

It was the year 1999, when I was still new to the wealth management industry. All I remember was everyone buying technology and Internet related shares and unit trusts.

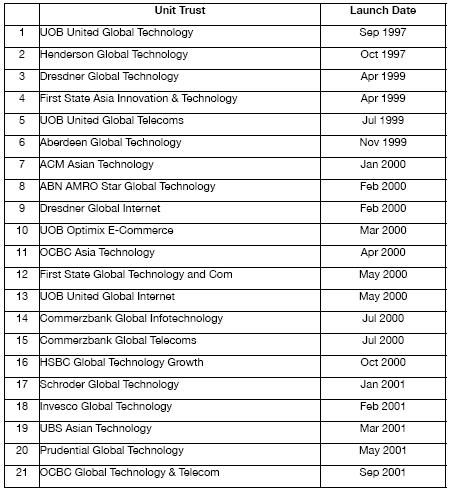

Even though Internet companies had no earnings to show at all, speculators flocked to them as long as they had a dot-com attached to their names. Even professional managers believed in them (see table below) and set up the bulk of Internet funds in 1999 and 2000. So how can it go wrong?

In mid-2000, the NASDAQ crashed.

So how does knowing the history of the stock markets help us?

Investment professionals always say: “This time is different”.

I disagree. I say there is nothing new under the sun.

History shows that “tulip mania” has repeated itself since the 17th century.

Greed will keep us buying even though prices are at a ridiculous high and will prompt us to sell in panic when we realize how ridiculous we have been.

Most of us never learn from history. We always succumb to that desire to make lots of money in the shortest period of time.

The Internet bubble has clearly shown that professionals are not always right. In fact, they could many times be wrong. How could fund managers, investment advisers, wealth managers, so called experts not know that those Internet stocks were selling at a ridiculous price?

Well, many probably knew, but they eagerly fed our greed, even as they satisfied their own desire, maximised profits and advanced their careers.

While we all hate to lose money, we dislike it even more when others are seemingly making lots of it and we are not. So we follow the crowd. When everyone sells in fear, we believe in the majority and follow suit. We don’t realize that that having a majority decision doesn’t always means the right decision and human sentiments have no bearing on the true value of businesses.

So how should we invest? Using the stock market history as a lesson, it is really not difficult to make money from investing. Find sound businesses with long term sustainability and at a reasonable price to invest in. Ignore the short term fluctuation as it has nothing to do with your businesses. Ignore what professionals tell you, especially those who make more money selling you than advising you.

Ignore the noise

Invest in the stocks for the long term. Sound simple? Well it is really that simple but unfortunately not easy. Many may not know how to identify good businesses. Short term fluctuations may cause us to lose sleep and give us ulcers.

To avoid having the need to pick the right stock, buy all the companies in the stock market through a low cost index fund or ETF. If you dislike the fluctuations, diversify your investments over different geographic regions and asset classes.

Ignore short term noise as the human greed and fear has absolutely nothing to do with your long term investments. In fact, if you are a long term investor and a net saver, you would rejoice when the market falls as it presents you with a chance to buy at a bargain price.

When the market is rising wildly, you would be sad as there is no opportunity to save. If you have to listen to a professional, make sure you choose one that takes care of your long term goal rather than fulfill his own short term ambitions.

How would you know? And how can you ensure that he delivers what he promises? Instead of paying him huge commissions for each product he sells you, put him on a regular payroll instead. Remove him if he cannot do the job. We are compensated this way too, so why should we pay our advisers differently?

So should you be worrying too much about the current sub-prime crisis, credit crunch, commodity inflation, the US inflation, etc? Having gone through the Asian financial crisis, the Internet bubble, SARS, the Iraq war, the oil price surge over the last 10 years or more, and having read the history of the market for the last 300 years, I can tell you this: Just as the sun will rise from the east and set in the west, the market will fall and rise once again. It has always been and it will always be. If you have done your investments correctly, sleep well. Tomorrow is a new day.

Christopher Tan is chairman and CEO of Providend, an independent private wealth management company that manages over S$250 million of assets (www.providend.com).