AFTER A long drive from San Francisco, Mr Franky Fan, his wife and son were holidaying in Seattle when he received a call from his China office: “Come back quickly. A government VVIP will visit our factory.”

Within hours, Mr Fan and family were in the air headed back to Hong Kong, their home city. The next day, at his factory in the Chinese industrial city of Dongguan, about two hours’ drive from Hong Kong, Mr Fan and his staff waited in anticipation for the arrival of the VVIP.

For security reasons, they were not informed who exactly it would be. They only knew when the motorcade arrived and out stepped Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, who was visiting several factories in Dongguan that day.

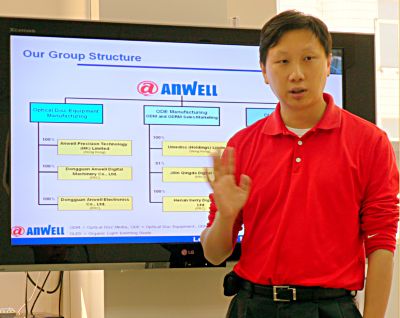

For Mr Fan, the executive chairman and CEO of Singapore-listed Anwell Technologies, the VVIP’s visit last July was symbolic of the country’s support for its high-tech companies.

Anwell is the world’s second largest manufacturer of equipment that replicates CD Roms, DVDs and Blu-ray discs – and is venturing into a key resource industry.

“The Prime Minister encouraged us to work hard on our new solar project,” recalled Mr Fan.

Mr Wen reportedly said to Anwell staff: “Solar panels are a key component of clean, renewable energy, which is an important direction for our power generation and energy industries. Thus, China looks to you for its power-saving and new energy infrastructure.”

As of early June 2009, China was getting ready to throw its economic might behind a national solar power plan that could make it one of the world's biggest harvesters of the sun's energy.The government body responsible for overseeing energy policy had finalised a proposal for billions of dollars of incentives for solar farms and rooftop panels.

Anwell will be riding on that wave: Harnessing the common technologies used for both optical disc and solar panel manufacturing equipment, it is developing manufacturing lines to produce solar panels that convert sunlight into electricity.

After investing over HK$100 million to start a venture in Henan province, it will start mass-producing solar panels in the second half of this year. Anwell has become one of only four companies in the world that designs and produces fully integrated production lines for thin-film solar panels.

After the Prime Minister’s visit, Anwell’s earlier application for government grants was approved. The company received more than RMB200 million for its research and development of a manufacturing line to produce OLED panels.

OLED panels, which are ultra-thin, are replacing LCD and plasma screens on consumer gadgets such as television sets and laptops.

There is a picture that Mr Fan treasures of himself accompanying the Prime Minister on the tour of Anwell’s factory. The picture, I noted on my recent trip to Anwell along with several analysts from Singapore, takes pride of place not just in Anwell’s factory in Dongguan but also its solar factory in Henan and its corporate headquarters in Hong Kong.

In the picture, Mr Fan is wearing a short-sleeved blue shirt sans a tie. The low-key dressing is evident too in his pictures on Anwell’s website and online newsletters, where he wears either a long-sleeved shirt with rolled-up sleeves or simply a long-sleeved jersey.

When I remarked on that, he said: “To put on a jacket, that’s not Franky. I like to go with my own style, my own thinking.”

He has also done it his way in his choice of work – by co-founding Anwell in 2000. He had left his US$15,000-a-month job as an engineering director in HHODL, Hong Kong’s largest manufacturer of CD-ROMS – the only employer he had ever worked for.

“The industry was suffering a slump at that time, and we thought sooner or later, we would lose our jobs,” recalled Mr Fan, who was aged 31 then, and decided to start his own business. “I knew that in a year or two, when the industry recovered, I would enjoy the harvest.”

Mr Fan had long wanted to be an entrepreneur and had made this known to anyone who cared to ask. “When I was in school, I prayed for a vision of my future. An image came to me: I was standing on top of a hill and below was a town full of my factories. From age 17 or 18, I knew I would be an entrepreneur one day. I told my girlfriend, whose is my wife now: ‘Now, I have nothing, but one day I will be very rich.’ ”

During a holiday stint with HHODL while he was mid-way through his PhD course, he proved himself so impressively that the boss interviewed him for a permanent job.

“I told him my ambition was to be my own boss one day,” remembered Mr Fan, who was hired anyway – as engineering director at the age of 25 of Hong Kong’s largest manufacturer of CD-ROMS.

The US$10,000-a-month salary he was offered was tempting, so he quit his course. Engineering flair runs within his family, it would seem, as his father was an engineering professor in a university in China.

The junior Fan had something else that became apparent later on: an ability to speak persuasively. This, as he revealed, came partly from being a debater in school and university.

“If I weren’t an engineer, I would be a lawyer,” he said, adding that passion and knowledge were also key to being convincing, not just talk.

When Mr Fan started Anwell in 2000, he had sufficient savings to tide his family through uncertain times as he built up Anwell. He was already married to his former schoolmate, Grace, and had a five-year-old son.

His wife’s job as a teacher provided stability of income – a fact that did not happen by chance as he had told her in the early days of their courtship that, given his entrepreneurial ambition and the volatility of earnings especially in the initial years, it would be good that she held a teacher’s post.

Pooling US$100,000 with some colleagues, Mr Fan started Anwell with two ex-HHODL engineers and 18 other staff (today, they have 2,500 employees).

Operating out of 7,000-sq ft of leased space in a factory in low-cost Dongguan, they designed machines that mass-produced CD-ROMs. As Mr Fan was well known in the industry, his team’s first design found a buyer without too much difficulty.

Anwell went on to overcome hurdle after hurdle – especially the notion among potential clients that made-in-China equipment could not match Western technology. In time, its equipment proved to be superior, with an output that is at least 20 per cent faster than any other similar disc replicator in the world, according to Anwell.

Despite its technological prowess, Anwell, which listed on the Singapore Exchange in 2004, has had a tough time making good profits consistently as demand for its equipment is cyclical, and research and development costs are high.

Last year, it raked in HK$905.4 million in sales but suffered a net loss of HK$101 million. The results include the first set of full-year contribution from its acquisition of a customer which produces optical discs.

With the acquisition, Anwell became the only manufacturer of replicating equipment and optical discs in the world.

Recently, striking out into the potentially lucrative renewable energy industry, Anwell has completed the construction of a sprawling factory (680 acres) in Henan province in China to build solar panels – a journey which began in August 2007 when Mr Fan and his team decided to further leverage on Anwell’s existing know-how.

Mr James Lim, an analyst from DMG & Partners, was among those who traveled to Henan to be updated on the solar project. He later wrote a report, saying: “We believe that Anwell had organised this plant trip mainly to show analysts that its solar business is not just some fabricated concept, given that some local investors have already been burnt during the debacle pertaining to Rowsley during late 2007. Coincidentally, Rowsley was also said to be dealing with thin-film solar cells back then.”

Top Henan government officials have visited the solar factory several times too and have pledged support for its smooth launch, according to Anwell.

But what about the risks of investing a tonne of money into this industry? Said Mr Fan: “I don’t think there’s too much risk. Our team has experience in developing similar systems. We are also supported by some national laboratories in China. From day one, I knew we could be successful.”

While developing its solar plant, Anwell has been marketing its capabilities at exhibitions and to potential customers. As a result, it has signed Memorandums of Understanding to supply clients with solar panels over the next few years.

In the second half of this year, Anwell will apply for the necessary certification that will enable it to sell to Europe and the US. “This will take about six months – but that doesn’t mean we cannot sell our solar panels during that time. We can sell to other markets and to solar farms, which don’t require the certification,” said Mr Fan.

The demand is there for Anwell’s panels as the company enjoys cost advantages from being the producer of its own equipment. In addition, said Mr Fan, the company’s solar panels are of the ‘thin-film’ technology, whose production cost is only a third that of the conventional crystalline silicon variety.

While Anwell currently has a production capacity of 40 megawatts a year, it will rapidly scale up to 1,000 megawatts by 2013 and become one of the world’s top 10 producers.

The solar venture holds the key for Anwell to become a very profitable company as the solar industry is potentially massive vis-a-vis the optical disc industry.

Mr Fan explained: “The solar industry will be around a long time because the sun will be the source of energy after fossil fuel runs out. But the optical disc industry cannot last for generations.”

“I have always thought we have a bright future. That’s why I have not sold a single share since Anwell’s IPO, and I have no plans to do that.”

If he was going to be very rich at some point in the future, I wondered how he would use the money.

“I don’t need a lot of money, as long as I have enough for my family. If you have a lot, you are just looking after it for the gods as you cannot take it with you when you die. My idea is we should use our surplus money to help others.”

To support the victims of the Sichuan earthquake last year, Anwell raised HK$1 million from its staff, with the management contributing about a month’s salary on average, said Mr Fan.

The staff also contributed funds to build a primary school which was completed last year for over 600 students in Henan province, where it operates its solar panel factory.

Mr Fan said: “On average, every year 15-20 per cent of my income goes to charity – such as some children’s charity of the United Nations - and another 17 per cent goes to income tax. I won’t pass a lot of money to my son. It’s better that I give him knowledge and motivation, and he can make money himself.”

I asked how he motivated his staff. “I work hard and that sets an example for them. I always consider myself an equal to them. We eat together in the office canteen, we fly economy together. My staff know that I donate money to charity and I motivate them to donate too,” he said.

This story was recently published in Pulses magazine and is reproduced here with permission.

Recent story: ANWELL produces its first solar panel