The following content is republished with permission of the author, Jim Chuong, 39. He is a private investor based in Mississauga, Canada, and has been interviewed in MoneySense magazine, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star, CP24, and Report on Business Television. His interviews can be found on his website at http://www.ticonline.com

He is not certified as a financial planner nor does he have a securities designation or business degree. The information provided by Jim Chuong is not to be construed as investment advice.

Jim Chuong (standing, extreme right) and wife with Singapore friends after attending the Berkshire AGM in Omaha. NextInsight photo

Jim Chuong (standing, extreme right) and wife with Singapore friends after attending the Berkshire AGM in Omaha. NextInsight photo

THE RICH GET RICHER

Since high school, I discovered that I was quite lazy. This trait has manifested itself in my investing as I continue to try and find ways to build a fast growing portfolio with as little research, maintenance and tax consequences as possible.

I follow a fundamental premise when investing. To invest any other way requires far more knowledge and research.

My method is difficult to follow because, for most individuals, investing is a very ego-driven endeavor – individuals need to feel that they did well because of the work and research they did and the actions that they took. I don’t care about all that. My method is copy-and-do-nothing. All accolades can be given to the entrepreneurs and employees who run the businesses in which I hold stock.

"Long ago, Sir Isaac Newton gave us three laws of motion, which were the work of genius. But Sir Isaac’s talents didn’t extend to investing: He lost a bundle in the South Sea Bubble, explaining later, “I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men.” If he had not been traumatized by this loss, Sir Isaac might well have gone on to discover the Fourth Law of Motion: For investors as a whole, returns decrease as motion increases." – Warren Buffett

My baseline premise for stock investing is straight-forward: the rich get richer. The. Rich. Get. Richer.

I believe this to be true. Others may not.

I know that if a wealthy individual has millions of dollars, they will want tens of millions. If they have tens of millions, they will want hundreds of millions. If they have hundreds of millions then they will want billions, and so on and so forth. The ego demands it. A wealthy person will drive themselves (and those around them) to exhaustion in order to hoard money regardless of how much money they already have.

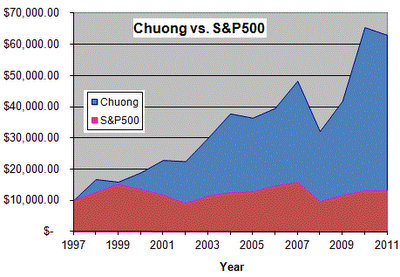

Jim Chuong's portfolio has outperformed the S&P.

Jim Chuong's portfolio has outperformed the S&P.

All I need to do is find one of these workaholics and ride their coattails and forget about everything else.

The public (stock) market is one place to find wealthy individuals. Combine this with the internet, and finding them can be done in a matter of a few minutes. Personally, I use the Yahoo! Finance Java-based stock screener. It’s quite robust and best of all, it’s free. With this tool I found that:

Jim Jannard owned 70% of Oakley (before he sold out to Luxottica), Roger and Michael King owned 50% of King World Productions (before they sold out to CBS), Dan Hirschfeld owns 40% of The Buckle, Tom and Kosta Kartsotis own 20% of Fossil, Gert and Tim Boyle own 60% of Columbia Sportswear, etc.

All of these individuals are extremely talented entrepreneurs and all these people once had millions, then tens of millions, then hundreds of millions, and then billions of dollars.

The addiction to hoard (money) is an extremely powerful instinct.

I’m a very poor entrepreneur, but I’m grateful that we live in a capitalistic society. In a capitalistic society I don't need to be intelligent, entrepreneurial or even hard working to make money. All I need to do is invest alongside a talented entrepreneur and I will reap the same benefits.

I don't need to run as fast as a horse in order to arrive at the same time as the horse. I just need to sit on the horse.

All I need to be able to do is put aside my ego’s desire to take credit for the financial success of these businesses or even for finding them. No problem.

Why did I choose the stock market as my vehicle as opposed to a private business, say, a car wash or hamburger stand? Probably laziness. Going to the library to go through Value Line sheets was easier for me as an anti-social teenager than seeking out local entrepreneurs and researching their companies.

There was also another problem.

If I went to a private business that made hundreds of millions in profit and asked to pay 8x earnings or 2x book to buy their business, they would kick me out the door - if they were nice. Thankfully, it doesn't work like that in the public market.

The owners of public companies can't stop me from buying their business on the cheap. Whether times are good or bad, everybody gets the same price. Everybody. The owners of the business have no say in the matter. The best they can do to drive away others is to buy the stock themselves – to hoard ownership. And they do - especially when prices are favourable.

99% of the time businesses are fully valued by the market. 99% of the time, I don't do anything. 99% of the time, it's boring. Just like the past couple years.

But when that 1% rolls around do I get excited! I become Jim Jannard's, Dan Hirschfeld's, Tom and Kosta Kartsotis's partner at a fantastic price!

Why should I sacrifice years of my life slaving away trying to start a business when there are more able, more intelligent, more driven, more entrepreneurial individuals already doing a better job than I could do with a 1000 lifetimes? Do I want to be the partner of a multi-millionaire entrepreneur for life? Sure. Why not?

HOW A 2.5% MANAGEMENT FEE TAKES AWAY HALF YOUR MONEY

Sometimes somebody asks me how a 2.5% MER or Management Expense Ratio is expensive? After all, if they “only” charge 2.5%, that means that unitholders get to keep 97.5% of the return. Right? Not exactly.

The problem is that the 2.5% fee comes off a compounding (and generally), single-digit return.

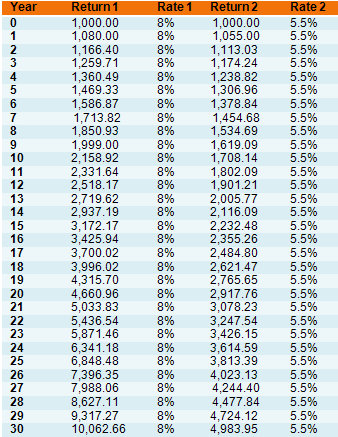

Let’s assume that a fictional fund that charges a 2.5% MER has an unrealistically stable return of 8% per year for 30 years. If this fund did not have a fee, the results would look like the “Return 1” column in the next graph. With a 2.5% fee, however, the return would be 8% - 2.5% = 5.5% per year for 30 years and the results would look like the “Return 2” column.

After 30 years, it becomes very clear that half of the money is gone as a result of fees. This means, that if an individual started investing at the age of 30, and wanted to retire at the age of 60, half of their money would have been taken by fees.

When people ask me how a 2.5% fee can be expensive, I tell them that paying half my money in fees, is too expensive for me. That’s just ridiculous.

CREDIT DOWNGRADE? WHO CARES?

People have been asking me about the global economy, as if I had a care about the global economy in the past. I don’t. I never cared about the global economy back then, and a I don’t really care about the global economy now. Why? Because it doesn’t determine if I make money or not. This topic is just salacious financial gossip similar to reading US Weekly or watching Entertainment Tonight - entertaining, but not particularly useful.

I also don't care about the how’s or whys of the US credit down grade from AAA to AA. I actually don't care about the how’s and whys of anything that affect the market.

I just want to make money. Knowing the how’s and whys of a market drop has never helped me make any money. But that's just me. I focus on the business. I want to read about the income statement and balance sheet. The market and causes of drops are irrelevant to me.

The Motley Fool has a few solid articles surrounding the dissection of financial statements. I enjoy reading those.

From my perspective, anything that can drop the entire market is good. I don't care if it's a down grade, mortgage backed securities implosion, riots in Greece, tech sector fallout, collapse of housing, whatever. All I am looking for is a system wide collapse.

Why? It's the absolutely easiest way to make money.

In a 'normal' or bull market economy, it is extremely difficult to make money. Prices are too high. And when prices are not too high, it's usually because the business that I'm looking at is going through a problem. And problems are difficult to diagnose as terminal or turnaround (see K-Swiss). At least for me it is quite difficult. My brain can only handle easy problems.

A market wide crash is an easy problem. I can have a spectacularly performing business that will simply collapse in sympathy with a meltdown. How easy is that? I already know that the business is healthy and I get to pick it up on the cheap! As far as I’m concerned, that’s pretty easy (cue pressing the oversized red Staples “Easy” button).

We should all hope that this down grade causes another market meltdown. Why work for money when the market can give it to you for free?

TO BUY OR NOT TO BUY, THAT IS THE QUESTION

I’m often asked how I decide to exit stock X in order to buy stock Y.

The short and easy answer is that I’m never looking to exit stock X to buy stock Y. My desire is to hold stock X forever and buy stock Y to also hold forever. For whatever reason, that answer never seems satisfy the questioner so perhaps I’ll expand it a little.

This question is actually composed of 2 unrelated questions. The first question involves when I would exit stock X and the second question is when I would buy stock Y. For me, the selling of stock X is never related to buying stock Y. Never. They are independent, mutually exclusive decisions.

With regards to selling stock X, I don't have an exit strategy. When I buy, I expect to hold for years. Decades ideally. However, there are factors that would cause me to sell including:

1. Needing the money for personal reasons

2. Significant reduction in insider ownership

3. Buyouts (King World bought by CBS/Viacom, Oakley bought by Luxottica, etc.)

The second question involves when I would buy stock Y. My criteria for selling (as outlined above) never involves buying another stock. Ever. I will buy stock Y if it is clearly better than stock X (i.e. same fundamentals, cheaper price).

If stock Y isn’t better than stock X it makes no sense to add stock Y to my portfolio. It would actually make more sense to add more of stock X. However, in most cases, stock X and stock Y are overpriced and I end up doing nothing.

WHY 6 STOCKS?

Another question I am usually asked is why I hold 6 stocks. Why not 10 or 20?

There is no fixed number in mind. It could easily have been 4 stocks. In order to understand how my portfolio has ended up with 6 stocks, one needs to understand the timeline of investing. What does this mean? It means understanding that buying a stock at one point in time is not the same as buying the same stock at another point in time.

Many things have usually changed including the business and the price. Just because I found a stock to be a “good deal” in 2002 doesn’t mean that it’s a “good deal” in 2003. Conversely, just because I found a stock to be a “bad deal” in 2006 doesn’t mean that it can’t become a “good deal” in 2008.

People often confuse my purchase of a stock as an endorsement of purchasing that stock at any time for any price. This is wrong. Dead wrong. You can lose a lot of money buying the stocks I've bought in the past – if you get the price wrong.

Another thing to consider is that buying my first stock has different dynamics than buying the 2nd or 3rd stock.

To buy the first stock is easy. I screen for insider ownership and financials. This usually leaves me with 2-3 dozen candidates. Then I rank them and I wait for prices to fall.

The wait is usually 3-5 years. During this time a crisis usually happens that takes the price down for some of the businesses.

I'll buy one of my top selections over the course of a year. Let’s call this stock X. After a year or so, the price of stock X usually rebounds and forces me to stop buying.

I resume waiting.

When the next crisis occurs a number of stocks fall in price. Even stock X may have fallen in price. At this point, I need to determine whether to add a new stock to my portfolio. Let’s call this potential candidate stock Y. I will only add stock Y if it is significantly better than stock X.

In order for stock Y to be better it must have the same financial characteristics and is cheaper than stock X.

If stock Y is not better, then it makes no sense to add it simply for the sake of adding it. It actually makes more sense to add more of stock X during this second crisis.

At a certain point (around 4 stocks) it becomes difficult for any new business to be better than all of the 4 that I already own. Usually one of the stocks in my portfolio will be a better pick than a prospective candidate. Over time it becomes increasingly likely that it is better to buy more of a company that I already own than to add a new one.

I may add a seventh stock, but it would have to be better than all the 6 others - which is not impossible, but very unlikely. There's a lot of money involved in doing nothing.

WHY NOT SELL OVERVALUED STOCKS TO BUY UNDERVALUED ONES?

This is a common question deserves an uncommon answer. The question itself is ridiculous because it assumes that when stock X becomes overvalued, another stock, Y, becomes undervalued, at the same time. If only the market gave us returns on a silver platter just like that.

Another problem is the definition of overvalued. What is that? When does it happen? If $10 is overvalued what is $11? Very overvalued? What is $14? Super overvalued? What is $20? Super duper overvalued?

There are three big problems when selling a stock based on it being “overvalued”.

The first is that the term “overvalued” characterizes the business at a single point in time. When somebody says stock X is “overvalued” they usually mean that the price is “overvalued” compared to current year earnings or book value. However, if the business is a strong one, would the price be “overvalued” compared to earnings or book value 10 years from now? Probably not. And that’s a huge problem.

Strong businesses can grow for a very, very long time. I can guarantee that there are businesses that exist today that will be around long after I’ve passed.

A second problem, which is somewhat related to the first, is that a successful business that exists on the exchange for many years will go through many periods of overvaluation in a year, let alone a lifetime. In which period of overvaluation do I sell? Do I sell during the overvalued period on January 15th 2000 or November 3rd 2009 or July 22nd 2014?

This leads me to my third problem which is watching a great company become better and better, but I’ve already left the party. There is nothing worse than buying in at a fantastic price and then selling, only to realize that the company went global and grew 20-fold. I can invest in a lot of duds (see K-Swiss) and still come out roses if I just avoid selling that one gem.

With the method that I use to invest, for every 10 stocks I buy, I will probably have 1 outstanding performer (see Fossil), 8 mediocre or good performers (see American Eagle, Columbia Sportswear, Oakley, King World Productions, Berkshire Hathaway) and 1 disaster (see K-Swiss).

|

WHY NOT LEVERAGE YOURSELF AND MAXIMIZE YOUR GAINS?

Once somebody discovers that I enjoy investing, the discussion inevitably turns to how I pick stocks to maximize my return. I don't believe in maximizing my returns as much as protecting myself from downside. "Worry about the downside, the upside will take care of itself." |

Jim Chuong's letter continues here

Under no circumstances does the information represent a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security or asset. Any and all references to "the portfolio" or "portfolio" refers only to his personal trading account. His website in no way offers or represents financial or investment advice. Information is provided for entertainment purposes only. Please read his disclaimer for more information.

Jim Jannard owned 70% of Oakley (before he sold out to Luxottica), Roger and Michael King owned 50% of King World Productions (before they sold out to CBS), Dan Hirschfeld owns 40% of The Buckle, Tom and Kosta Kartsotis own 20% of Fossil, Gert and Tim Boyle own 60% of Columbia Sportswear, etc."

Hi there, was just wondering, how do you get that information from Yahoo Finance?